There are 4,403 Paralympic athletes competing in Tokyo, each with unique disabilities that need to be classified to ensure fairness for all.

Athletes are grouped into classifications of similar disabilities or disabilities that yield similar results, reported the Washington Post.

It’s a confusing and complicated system. The Paralympics are competitive and athletes are well aware that no matter where a classification line is drawn, some are likely to benefit more than others.

Winning results in gold medals, sponsorship deals, and other outside funding. Some teams are known to recruit younger athletes in that top range of classification.

“The problem with the classification is that if you are at the bottom edge you are not happy,” said Heinrich Popow, a two-time gold medalist in track and field. “The athletes always want to have the best classification.”

Athletes without disabilities have advantages in certain sports, and athletes with disabilities are not different in this matter.

There are 10 disability groups in the Paralympics: eight involve physical disabilities, and the other two groupings are for visual and intellectual disabilities. But the 22 Paralympic sports adjust the groups to cater to their sport, swelling the classifications. Some athletes believe that’s not always fair.

“If we think we can swim or run the same times as everyone else, we feel good being in the class,” Popow said. “But if we feel we’re doing our best and can’t even reach the limit to qualify, or pass through the heats, you start to complain.”

The International Paralympic Committee (IPC) has just begun a regular review of the classification system, but changes aren’t likely to occur until after the 2024 Paralympics in Paris, spokesman Craig Spence said.

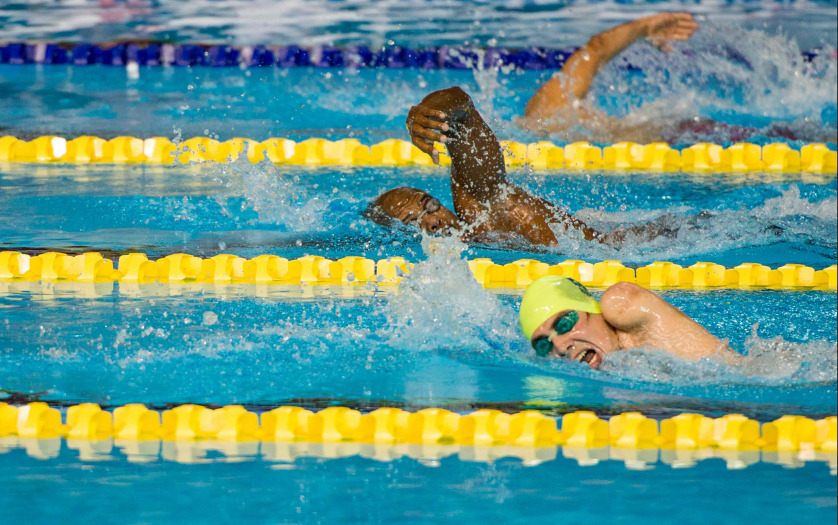

At a quick glance, the current classifications system is difficult to understand. For example, the finals in swimming on Saturday — each has a men’s and women’s race — include: 100-meter breaststroke, SB6 class; 100 freestyle, S10; 150 individual medley, SM4; 150 individual medley, SM3; 100 backstroke, S11; 200 individual medley, SM8; and 100 breaststroke, SB5.

Most athletes are in agreement that classifications are necessary, but they still may debate the logic behind them.

“To be honest, athletes don’t understand the system,” Popow said. “Every athlete just wants to focus on himself and his disability and class. We need to have a classification system overall that everyone understands.”

Tea Cisic, head of classification system for the IPC and a kinesiologist, has the responsibility of assessing the disabilities.

“They (athletes) are entitled to complain,” Cisic told The Associated Press. “They are entitled to come forward and say, ‘I’m not happy with my class. I think I’ve been incorrectly classified.’ And there’s a process for them to get reviewed.”

Cisic acknowledged the classification system is complex, but said fans need to make an effort to understand it, the way new fans might initially struggle to understand the rules of cricket or baseball.

”Classification is complex and it does require an investment from the audience to understand how it works,” she said. “But once you do that, I think it unfolds.”

The Paralympics are more than a mild version of the Olympics. In fact, a few performances are better than the Olympics.

Markus Rehm — known as the “Blade Jumper” — lost his right leg below the knee when he was 14 in a wakeboarding accident. Earlier this year, he jumped 8.62 meters, a distance that would have won the last seven Olympics, including the Tokyo Games. The winning long jump at this year’s Olympics was 8.41 meters.

Archer Matt Stutzman was born with no arms, just stumps at the shoulders. He holds a world record — for any archer, with or without a disability — for the longest, most accurate shot, hitting a target at 310 yards, or about 283 meters.

The largest classification contentions involve athletes with “loss of function” — spinal cord injuries, spina bifida, and cerebral palsy — rather than physical disabilities like missing limbs or physical deformities.

There seems to be fewer discourse over visible disabilities, like the loss of a limb. Coordination disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, tends to be questioned more.

But the eye is deceiving. Japanese swimmer Miyuki Yamada, 14 years old, won a silver medal this week in the 100-meter backstroke, S2 class. Yamada was born without arms and it seemed unfair to see her race against swimmers with arms. But yet, she won a medal.

Obviously, other swimmers had disabilities that were more difficult to see.

Popow, a two-time gold medalist who is retired and not competing in Tokyo, said the Paralympics might be reaching a point in which important decisions need to be made – decisions that could end up excluding athletes.

“The most important thing for us in the future is to clarity the question: Are we going to go for being a more professional sport, or are we going more for being a motivational sport for the society?” Popow asked.

“If we go more to the professional side, we won’t talk so much about inclusion because it will be exclusion. We have marks to be set. Athletes have to fulfil higher levels to attend the Paralympics.”