The University of Colorado Museum of Natural History has joined forces with educators and disability advocates to develop science education materials for children who are deaf and hard-of-hearing.

With the support of a $22,800 grant from the CU Boulder Office for Outreach and Engagement, the university’s team is working closely with specialists to craft complimentary lessons in archaeology, paleontology, and biology. These resources will be accessible online in American Sign Language, Spanish, and English for everyone’s benefit.

“The COVID-19 pandemic drove home in a relatively immediate and urgent way just how serious the impact is on all communities that are losing access to education resources,” says William Taylor, assistant professor of anthropology and curator of archeology at the CU Museum of Natural History.

“I think we observed that some of the communities that are hardest hit by the impact are those that are underserved to begin with.”

The idea to create science education tools in ASL, as well as Spanish and other languages, was a long time coming for Taylor and Cecily Whitworth, project co-directors and siblings.

Taylor and Whitworth, a former linguistics professor who now works in advocacy with Montana Family ASL, each brought a distinct perspective to the project.

Whitworth, who is deaf, says her approach to the project has roots in seeing how inadequate education resources affect deaf children in rural communities.

It’s not unusual for there to be only one deaf child in a rural town or school district, and with resources far away or otherwise inaccessible, language deprivation is “a huge problem,” Whitworth says.

While newborn-hearing screenings are the norm, deaf children can still miss out on weeks, months or even years of language acquisition before and after they’re identified.

“If the family lives a far distance away from a big city or maybe decides they don’t want to rely on ASL, the infant continues to miss out on a lot of typical language acquisition milestones, and that causes permanent problems throughout their life,” Whitworth says.

Rural communities may not have ASL classes or a deaf community to support families, Whitworth adds. That’s where online education resources for deaf children can start to bridge the gap.

Taylor says Whitworth’s experience is the reason he enters museums thinking about whether the content is being shared with the deaf community.

“The truth of the matter is that at most museums, especially smaller museums that struggle with funding, that are understaffed and reactive rather than strategic with their planning, the folks that get the short shrift with content, accessibility and science education are the disabled community,” Taylor says. “That’s true at every museum, but it’s also true at our museum.”

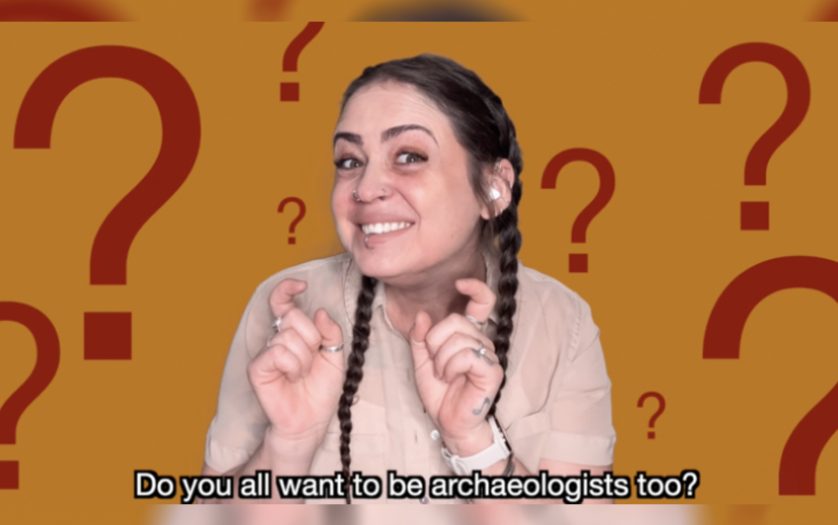

The program’s first lesson, “Let’s Talk About Archeology,” is aimed at children ages 4-7 and introduces them to Amelia Dall, an archeologist who is deaf, who talks about what archeologists do and what tools they need in the field. Dall uses ASL, and the video includes English captions.

Students can also learn ASL archeology vocabulary and fill out a worksheet.

Taylor and Whitworth developed the materials along with the museum’s archeology team, Montana Family ASL and other public-education experts, who met to decide what core concepts to introduce through the lesson and how to make it accessible for young children.

“One of the things about the project is we want to have it not just be an archeologist talking in ASL translation. We want deaf scientists and educators to present directly to kids, because there’s something special about learning it in their language,” Taylor says.

While the concepts being taught are simple, the lessons give kids a chance to encounter deaf scientists, Whitworth says.

“I think that’s where the potential long-lasting impact is of a project like this, to show people excellence and show them you can do this. Those hopes and dreams can get hard-wired when you’re really young,” Whitworth says. “Deaf, hard-of-hearing youth and other minority children often don’t think they can achieve those goals or do those jobs.”

In the coming months, the team plans to launch similar lessons for biology and paleontology, offer lessons in Spanish and potentially expand into other areas of study.

“Our hope with this project is we get other folks excited to develop resources for things like planetary sciences, engineering—there’s a whole diverse range of exciting academic fields and sciences,” Taylor says. “We want for folks to come forward and say, ‘We want to add our voice to this project.’”